|

By Hugo Campos, International Potato Center (CIP) |

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

Within the CGIAR, there is a flurry of activity, thought, discussions and even some (natural) uneasiness about how embrace change and modernize our breeding efforts.

As scientists and professionals, our instinct is to calculate and map out the way ahead, but science and technology is only the tip of the iceberg; lasting impact will come by first changing our behaviors, not the other way around.

At first glance, the task is daunting. Global trends such as climate change, increasing urbanization, food and nutrition insecurity make it imperative to modernize CGIAR breeding networks.

In the current funding landscape, we will be judged by our ability to increase genetic gains for key traits in the crops we work on, as well as the actual adoption of new cultivars in the field by smallholder farmers and by participants in crop value chains.

In order to make good on this promise, we need to embrace a truly disruptive level of change in our breeding networks. Instead of reinventing the wheel however, we can aggressively borrow learnings, and mistakes, from other industries and organizations. Among these we should prioritize an understanding of the principles of change management.

Experiences of change management in the corporate world are not encouraging. Most large-scale organizational change initiatives either fail, fall short of expectations, or consume far more resources or time than expected.

We can learn from these unsuccessful experiences, and it turns out most can be traced to the lack of ability to grasp the importance of people-based issues.

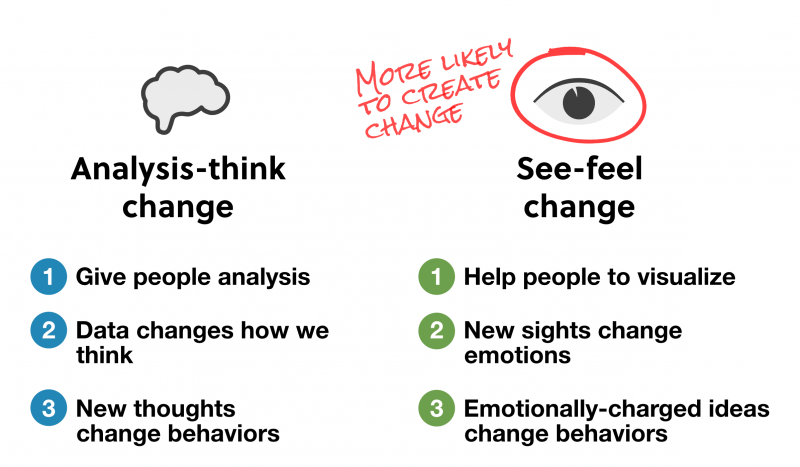

Current thinking in change management identifies two different approaches to change: that which is based in logic, and that which is based in emotion, as summarized below.

Comparing two approaches to change – logic and emotion (Adapted from Dan Cohen, The heart of change, Harvard Business Review Press)

Human beings are more likely to change as a result of compelling experiences that affect their feelings than as a result of hard data or evidence. This explains all the contradictions we display as individuals, such as the chain-smoking doctor or the divorced marriage counselor.

Just as change needs to be embedded at an emotional level to last, the modernization of CGIAR breeding programs is unlikely to be marked by a single episode of change. Instead, continuous change in our profession will become the new standard. Just think about the dramatic consolidation and change in the way plant and animal breeding is done in industry.

Many centuries ago, Plato stated that “in our heads we have a rational charioteer who has to rein in an unruly horse that "barely yields to horsewhip and goad combined."

The charioteer represents our rational mind, known as the reflective or conscious system. Meanwhile, the horse is our emotional side which is instinctive and aims to avoid pain and seek pleasure.

Our scientific and professional training makes us think of the charioteer, but even their flawless direction is not enough to change the course of the entire vehicle.

Just as we adopt new technologies and approaches, we should learn from the best practices from successful change management in order to succeed.

During following blogs, we will briefly discuss what is known about successful change management efforts and how such insights could be applied to the fascinating yet challenging task at hand, namely the modernization of CGIAR breeding programs.

Comments

Agricultural breeding has